If you are looking for new sources of inspiration, I’d like to introduce you to some distinctive artists, designers, and illustrators – both past and present – that I think ‘you should know.’ Some may be lesser-known while others may seem vaguely familiar, either way you will discover unique talents that might just influence your next design project.

The year is 1937 and Torchy Brown, a young, ambitious African American woman, is about to leave her small Mississippi hometown for the bright lights and opportunities of New York City. As she starts to board her train she notices a directional sign with arrows pointing to two different boxcars – one for white people only and one for “colored” people. After thinking for a minute, Torchy, with a grin on her face, decides to pretend that she can’t read and then boards the whites-only boxcar.(1)

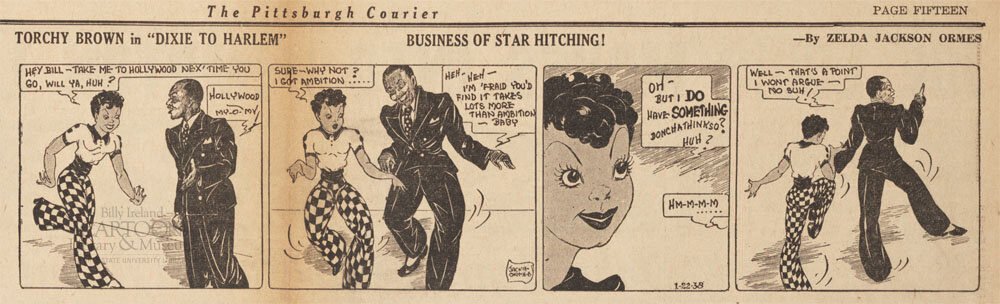

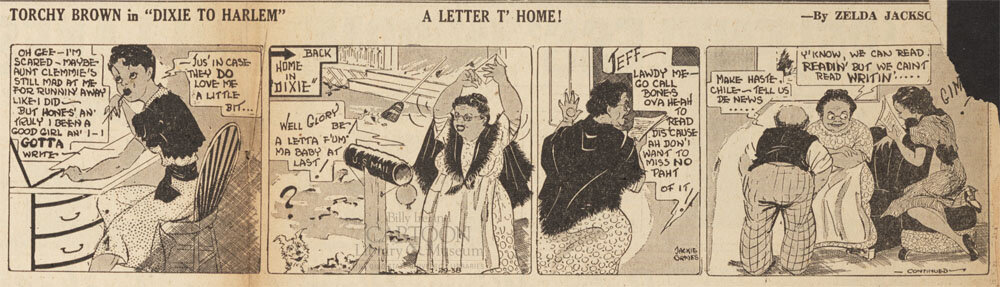

This type of politically charged scene was commonplace in the groundbreaking work of Jackie Ormes. The pioneering journalist, artist, and designer was the first African American woman to have a successful career as a professional cartoonist.(1) For almost 30 years, Ormes’ writings and cartoons were featured on the pages of the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier, and other leading African American newspapers of the early-to-mid 20th century.(2)

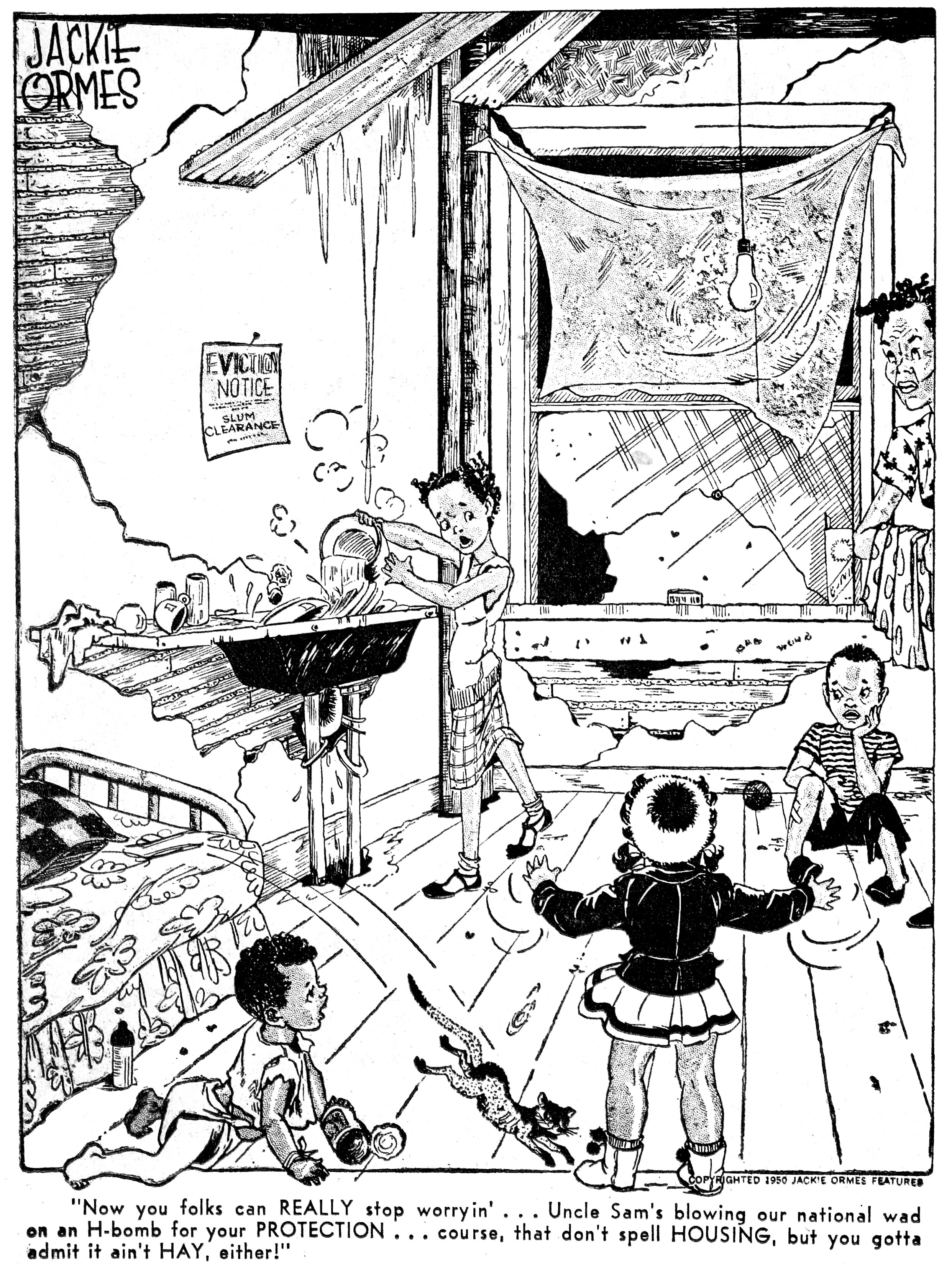

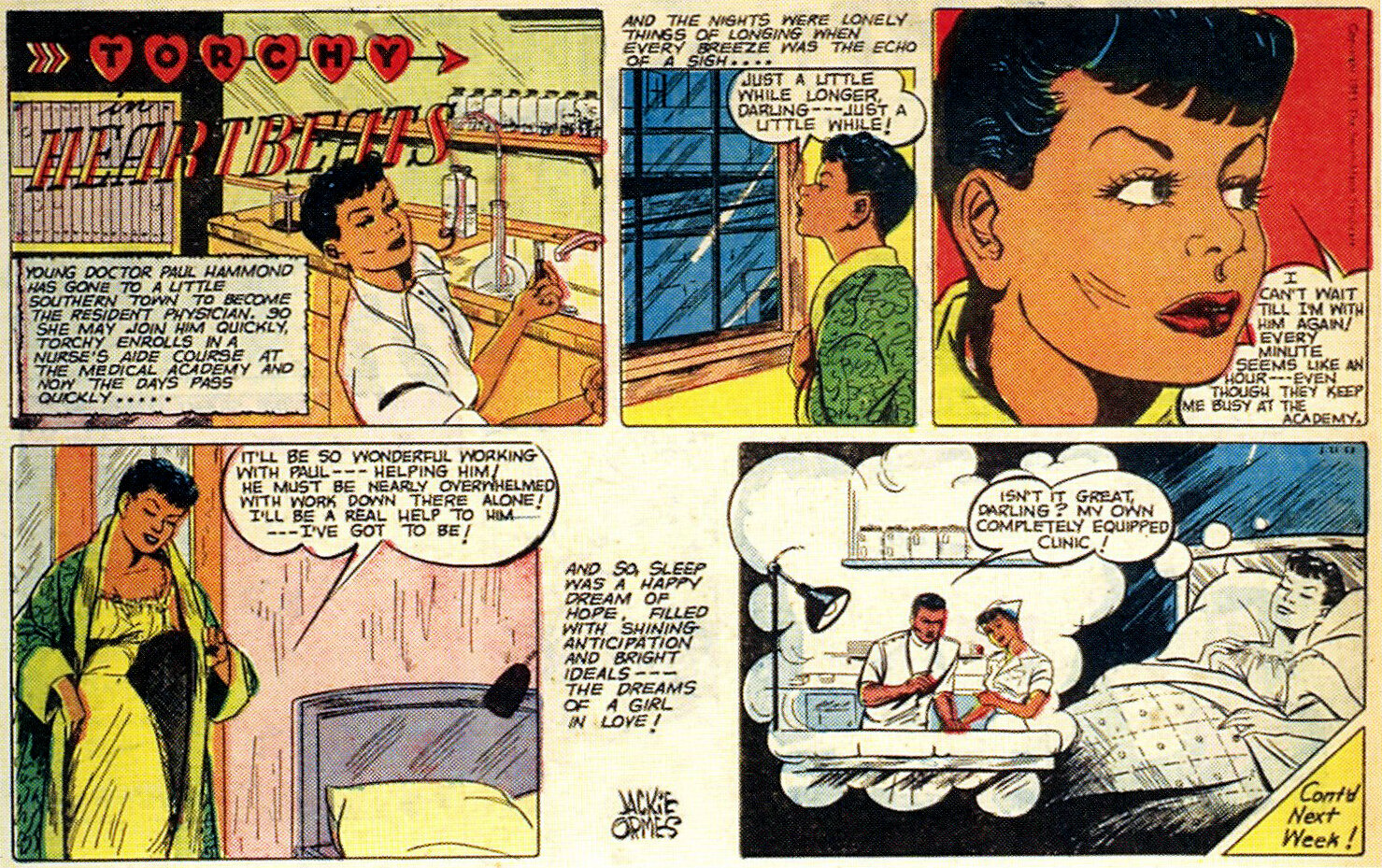

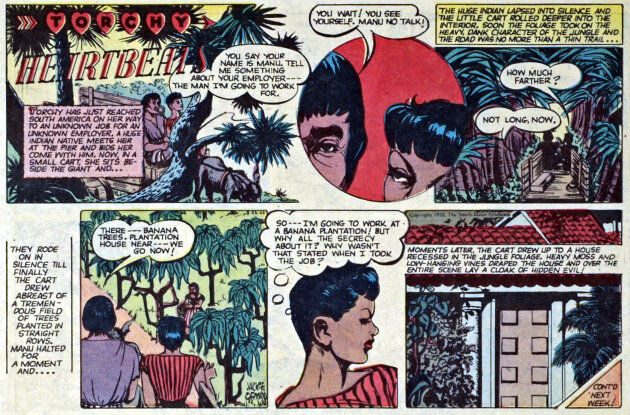

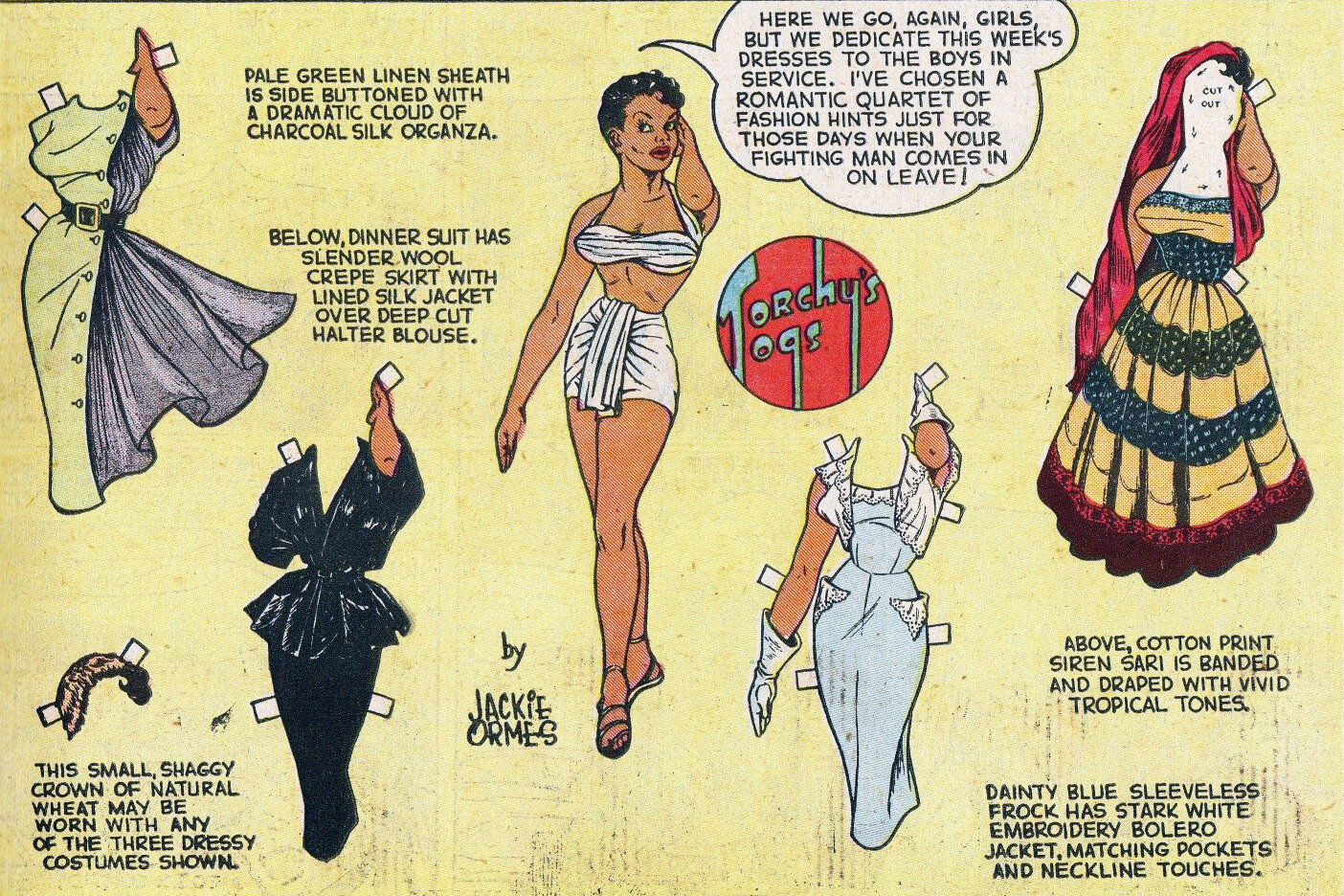

During her long and trailblazing career, Ormes created four innovative cartoon series – “Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem,” “Candy,” “Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger,” and “Torchy Brown in Heartbeats.”(2) At a time when mainstream media depictions of African Americans were frequently based on derogatory stereotypes, Ormes’ work stood out. Her characters were smart, fashionable, professional, and politically aware. She presented realistic depictions of hard-working, upwardly mobile African Americans.(3)

According to art historian Earnestine Jenkins, “Influenced by race, gender, and class, Ormes drew upon black women’s beauty practice and imagery to create characters that articulated self-pride and modernity. She rejected caricatures. She spoke ‘truth to power’ through everyday people and circumstances her readers recognized.”(4)

Ormes was by no means an imposing figure. Standing at only 5’2” and weighing around 100 pounds, she was petite by any measure of the word.(3) How did this African American woman find success in the male-dominated newsrooms of the 1930s-1950s? She did it with an abundance of talent and sheer determination.

Jackie Ormes was born Zelda Mavin Jackson in a small, middle-class community outside of Pittsburgh in 1911.(3) She was nicknamed “Jackie,” based off of her surname. At the tender age of six-years-old, her father died suddenly. With her older sister, she went to live with her grandmother while her mother found work as a live-in maid to help support the family. Despite family tragedy and financial hardships, the young Jackson girls were encouraged to pursue their education and foster their natural talents.(2) During high school, Ormes began writing for the Pittsburgh Courier. Following graduation, they hired her as a proofreader and cub reporter. In 1936, at the age of 25, she married Earl Ormes. The following year the self-taught artist had her first cartoon published by the newspaper.(2)

The “Dixie to Harlem” cartoon followed twenty-something Torchy Brown as she pursued her career as a nightclub performer at the famed Cotton Club in Harlem. Filled with comedy and action, Torchy’s adventures included encounters with famous entertainers of the day like Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Despite the societal challenges of being an African American and a woman in 1930s America, Torchy found success through her own mix of intelligence and talent, much like her creator.(2)

In the early 1940s, Ormes moved with her husband to Chicago. While Earl Ormes began managing the Sutherland Hotel, an upscale hotel for African Americans, she began writing a society column and assorted news articles for the Chicago Defender. In 1942, she started a new one-panel cartoon entitled “Candy.”(5)

Ormes once again found inspiration from her own life while developing the character of Candy. Presumably modeled after her own mother’s experiences, the “Candy” cartoon followed the day-to-day life of a young, humorous maid who worked for the never-seen “Mrs. Goldrocks.”(6) Candy was a hard-working woman who was not afraid to use her quick wit to speak her mind. Although only running for four months,(4) the cartoon made an impact during the World War II era – tackling issues important to the African American community. The cartoon also set the tone for Ormes’ next project.

Following the loss of her only child to a brain aneurism at the age of four, Ormes began what would be her most successful cartoon series.(2) In 1945, she resumed her relationship with the Pittsburgh Courier when she produced the “Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger” series. The cartoon centered on the life of a little girl named Patty-Jo and her guardian and older sister, Ginger. The child, who was opinionated and wise beyond her years, served as the cartoon’s sole narrator. The Ginger character, although silent in the series, was a college-educated, working professional with an eye for fashion. She served as a role model and occasional comedic foil for her younger sister.(2)

Ormes channeled her personal grief into forming the clever and precocious child protagonist, Patty-Jo.(2) She also found inspiration in her own relationship with her older sister and their experiences living rather independently following the death of their father. In addition to the strong personal connection Ormes had for these two characters, she also used the series to address major societal struggles of post-war America. The pint-sized Patty-Jo commented on everything from civil rights and poverty to McCarthyism and the nuclear arms race.(7)

Ormes created over 500 cartoons in the “Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger” series during its 11-year run.(4) The series was so popular that in 1947 the Patty-Jo character was turned into a doll, produced by the Terri Lee Doll Company. Unlike many other African American dolls of the time, the Patty-Jo doll was not designed in a racially derogatory manner. Instead, she was one of the first upscale African American dolls to be mass-marketed. With hair that could be styled and an extensive wardrobe for all occasions, the Patty-Jo doll was remarkably innovative in its day. Only manufactured for two years, the Patty-Jo doll is now a highly sought after collectible.(8)

During the long run of “Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger,” Ormes also revisited her original character of Torchy Brown. In 1950, she embarked on designing a multipanel comic strip called “Torchy Brown in Heartbeats.” The comic strip was often accompanied with a paper doll series called “Torchy’s Togs,” which included modern fashions designed by Ormes.(6) Compared to the earlier incarnation, this version of Torchy was even more adventurous and socially aware. As she sought out love in the big city, Torchy dealt with issues of racism, sexism, and even environmental pollution. The popular comic strip was nationally syndicated, appearing as a feature in 14 newspapers.(2)

Following retirement from her cartoonist career in 1956, Ormes continued to pursue art and support artistic causes. She became a respected muralist and portrait painter. Additionally, she served as a board member for the DuSable Museum of African American History in Chicago.(5) Despite her pioneering contributions, Ormes died at the age of 74 largely forgotten. Only recently have people started to rediscover her – with a whole new generation of cartoonists, artists, and designers learning about her remarkable story.(2)

As African American cartoonist Barbara Brandon-Croft stated, “Ormes paved the way … working as a journalist, struggling to make a way in the ‘man’s world’ of cartooning, and addressing in [her] cartoons a range of issues still with us.”(9)

Sources

1 Norris, Kyle. “Comics Crusader: Remembering Jackie Ormes.” All Things Considered. 29 Jul. 2008. NPR. Web. 30 July 2020. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=93029000

2 Williams, Jasmin. “Meet Jackie Ormes and Torchy Brown.” New York Amsterdam News. 1 Aug. 2012. Amsterdam News. Web. 30 July 2020. http://amsterdamnews.com/news/2012/aug/01/meet-jackie-ormes-and-torchy-brown/

3 Goldstein, Nancy. “Jackie Ormes: The First Female African American Cartoonist.” University of Michigan Press, 2008.

4 Jenkins, Earnestine. “Jackie Ormes: The First Female African American Cartoonist (Review).” Project MUSE. Summer 2009. Web. 30 July 2020. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/419720

5 Kelly, Kate. “Jackie Ormes (1911-1986), First African-American Female Cartoonist.” America Comes Alive. 22 Oct. 2013. Web. 30 July 2020. https://americacomesalive.com/jackie-ormes-1911-1986-first-african-american-female-cartoonist/

6 Wolk, Douglas. “Origin Story: Jackie Ormes.” The New York Times. 30 Mar. 2008. The New York Times Company. Web. 30 July 2020. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/30/books/review/Wolk2-t.html?_r=1&

7 Onion, Rebecca. “Fifty Years Before Boondocks There Was Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger.” Slate.com. 13 Aug. 2013. The Slate Group. Web. 30 July 2020. http://www.slate.com/blogs/the_vault/2013/08/13/_patty_jo_n_ginger_the_ground_breaking_african_american_cartoon_of_the_1940s.html

8 Goldstein, Nancy. “Jackie Ormes: The First Female African American Cartoonist (Patty-Jo Doll).” JackieOrmes.com. 2008. Web. 30 July 2020. http://www.jackieormes.com/pattyjo.php

9 Goldstein, Nancy, et al. “Jackie Ormes: The First Female African American Cartoonist (Reviews).” University of Michigan Press. 2008. Web. 30 July 2020. http://www.press.umich.edu/script/press/150236

Ormes, Jackie. Assorted Images of Jackie Ormes and the Ormes’ Cartoon Series from above sources and the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at The Ohio State University (https://cartoons.osu.edu).